[ad_1]

Venture Capital Guide – An Introduction

Welcome to the Venture Capital Guide. As the number of start-ups is increasing in India, budding entrepreneurs are constantly looking for funding opportunities to scale up their operations. Venture Capital funds are playing a vital role in the growth of the start-up ecosystem in India.

A Venture Capital fund is an investment fund that provides funding to small & medium-sized enterprises in the form of private equity. The funds are created as an investing vehicle wherein investors pool their funds with an intention to acquire private equity stakes in start-ups & SMEs having high growth potential. A VC fund is often considered to be a high-risk/ high-return fund due to its investment portfolio consisting of risky early-stage start-ups & SMEs.

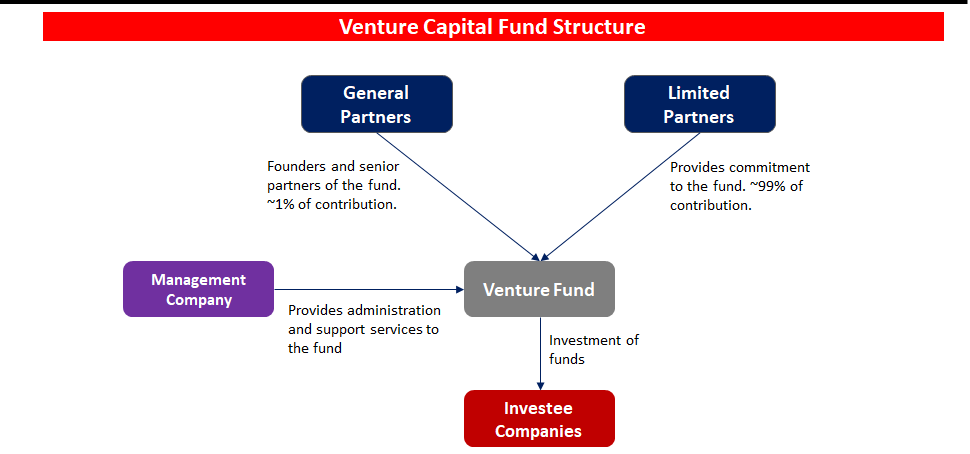

Overview of a Typical Venture Capital fund structure

Let’s start by discussing a typical Venture Capital fund structure (see illustration). A basic Venture Capital fund structure comprises of four entities.

The first entity in the structure is the Management Company which is generally owned and administered by the founders of the fund. The management company employs people with whom one interacts at the firm, such as the partners, associates, and support staff, etc. Thus, the management company is essentially the franchise of the firm. Even when the old funds are retired and new funds are raised, the management company continues to exist and service each of the funds that are raised.

The second entity is one that the Start-ups are rarely aware of, and it is called the General Partners (GP) entity. This is the legal entity for serving as the actual general partner to the fund. This entity is formed by the founders of the firm to act as a partner to the fund.

The third entity is one that pools the investment from various investors and commits to the Venture Fund, and it is called the Limited Partners (LP) entity. This is the legal entity for serving as the investment partner to the fund. When a Venture Capitalist talks about his “fund” or that his firm “raised a fund of $500 million” he is actually talking about an Investment Vehicle that has a commitment of $500 million from the investors.

The last entity is the Venture Capital Fund itself which is generally incorporated in the form of a Trust or a limited liability partnership. General Partners and Limited Partners acts as the partner of the Venture Capital Fund.

Also, generally the LPs want the VCs to invest some initial capital in their own fund. Generally, there has been a 99 percent/1 percent split between the LPs and the GPs, where the VC partners put in their own money alongside the LPs for 1 percent of the.

The key point to remember is that there is a separation between the management company and the actual funds that it raises. These distinct entities will often have varied interests and motivations, especially as managing directors of a VC fund may exit the VC firm. One managing director that is a point of contact today for an investee, may have different alignments among his multiple organizations.

Who are the typical investors who commit funds to a Venture Capital Fund?

The VC firms generally raise funds from various entities, including government organizations, pension funds, large corporations, banks, NBFCs, foreign institutional investors, high net-worth individuals, insurance companies, etc. The arrangement between the VC firm and its investors is subject to negotiations over a long & comprehensive contract known as the limited liability partnership agreement.

How do Venture Capitalists generate income?

Now that we’ve discussed a typical VC fund structure, let’s discuss how the VCs generate income. Generally, a VC generates income through the following:

1. Management Fees

A Venture Capital firm typically earns a percentage (varying from 1.5% to 2.5% of the total amount of money committed to a fund as management fees. The fees are taken annually and helps in financing the operations of the Venture Capital firm, including all the salaries for the investing partners and their employees. For example, if a VC firm raises $50 million funds with a management fee of 2%, every year the firm will receive $1 million in management fees. This may look like a lot of income from just one fund, however, it is usually exhausted in paying all of the fixed and variable costs of the VC firm, including rent, salaries, marketing and admin expenses, etc.

The percentage is usually inversely proportionate to the size of fund i.e. smaller the fund, the larger the percentage. This fee usually begins to decrease after the end of the commitment period. The formula varies widely, but in most firms, the average total fee over a 10-year period is about 15 percent of the committed capital. So, in case of a $150 million fund, the Management Company will have $7.5 million of management fees to run its operations and pay its people.

Since most VC firms raise multiple funds, the management fees are a substantial return for the Venture Capitalists. A medium-sized firm raises a new fund every three or four years, but some firms raise funds more frequently while others have multiple different fund vehicles such as an early-stage fund, a growth-stage fund, etc. In these cases, the fees stack up across funds. If a firm raises a fund every three years, it has a new management fee that adds to its old management fee. The simple way to think of this is that the management fee is roughly 2 percent of total committed capital across all funds. So, if Fund 1 is a $50 million fund and Fund 2 is a $100 million fund, the management fee will be approximately $3 million annually ($1 million for Fund 1 and $2 million for Fund 2).

The VC firm gets this management fee completely independently of its investing success. Over the long term, the only consequence of investment success on the fee is the ability of the firm to raise additional funds. If the firm does not generate meaningful positive returns, over time it will have difficulty raising additional funds. However, this isn’t an overnight phenomenon, as the fee arrangements for each fund are guaranteed for 10 years. We’ve been known to say that “it takes a decade to kill a venture capital firm,” and the extended fee dynamic is a key part of this.

2. Carried Interest

Even though the management fees can be substantial, in a success case the real money that a VC makes, known as the carried interest, or carry, can make the management fee look like only a minor return. Carry is the profit that VCs get after returning money to their investors (the LPs). If we use our $100 million fund example, VCs receive their carry after they’ve returned the capital committed amount to their LPs. Most VCs usually gets 20% of the profits after returning committed capital, although some big and successful funds take up to 30% of the profits made.

For example, a VC fund starts with an amount of $200 million. Let’s say, the investment made by the VC Fund is a success and the fund generates three times return on the capital contributed i.e. $600 million. In this case, the first $200 million will go back to the LPs, and the remaining profit of $400 million, is split 80 percent to the LPs and 20 percent to the GPs. The VC firm gets $80 million in carried interest and the LPs get the remaining $320 million. This is a favorable position for all the parties involved.

However, we know that this firm charges management fees from the fund which may lead to a reduction in funds available to invest. In order to avoid such a situation, VCs are allowed to recycle their management fee and subsequently reinvest in the fund itself, thereby creating a capital contribution of the firm.

How Time Impacts Venture Capital Fund Activity

VC fund agreements generally have two important clauses that govern the ability to invest over time. The first clause is called the commitment period. The commitment period may also be known as investment period, is the period that a VC has for identifying and investing in new companies in the fund. Once the commitment period is over, the fund can no longer invest in new companies, but it can invest additional money in existing portfolio companies. This is one of the main reasons that VC firms typically raise a new fund every three to five years—once they’ve committed to all the companies they are going to invest in from a fund, they need to raise a new fund to stay active as investors in new companies.

The other clause is called the investment term, or the length of time that the fund can remain active. New investments can be made only during the commitment/investment period, but follow-on investments can be made during the investment term. A typical VC fund has a 10-year investment term with two one-year options to extend, although some have three one-year extensions or one two-year extension. Twelve years may sound like plenty of time, but when an early-stage fund makes new seed investment in its fifth year and the time frame for the exit for an average investment can stretch out over a decade, 12 years is often a constraint. As a result, many early-stage funds go on for longer than 12 years—occasionally up to as many as 17 years.

In some cases, entire portfolios are sold to new firms via what is called a secondary sale in which someone else takes over managing the portfolio through the liquidation of the companies. In these cases, the people the entrepreneurs are dealing with, including their board members, can change completely. These secondary buyers often have a very different agenda than the original investor, usually much more focused on driving the company to a speedy exit, even at a lower value than the other LPs.

Hope this Venture Capital Guide is useful to you!

Investment Banking 101 – What is an investment Bank and what are its functions?

[ad_2]